Blog

Tool calling is broken without MCP Server Composition

December 1, 2025 - Roy Derks

MCP gives agents access to tools, prompts, and resources, but as a developer building AI applications I find tool calling is the part that actually changes how we build AI systems.

While the Model Context Protocol (MCP) provides a solution to exposes these capabilities without hard‑coding functions or rewriting integrations for each agent framework, it doesn’t tell you how agents should decide which tools to call or how those tools should be organized. Especially, when you need to combine tools from different MCP servers in your agents.

Anyone who has built APIs before will immediately feel nostalgic as these aren’t new problems. Just like backend engineers eventually created Backend‑for‑Frontends (BFFs) to cleanly expose functionality, and just like frontend teams adopted GraphQL to unify scattered data sources, developers building MCP servers need similar architectural layers.

This post is about how MCP server composition provides that missing layer using four patterns I keep seeing in real‑world agent systems for structuring, grouping, and orchestrating tools so that tool calling is no longer broken.

Why does tool calling often fail?

Tool calling doesn’t usually fail because "LLMs are bad at handling tools.” It fails because we overload the model with too many tools or badly designed tools. In my previous blog post (“Stop Converting OpenAPI Specs Into MCP Servers”), I explained why dumping an entire OpenAPI spec into MCP makes tools impossible for a model to handle. Let’s focus on the first problem: how having too many tools can break your agent.

Tool calling fails because of context bloat

Tool calling fails because of context bloatTools overload the context window

Every LLM has a fixed context window of let's say 8k, 32k, 128k, or even 1M tokens. That window must fit:

- The system prompt

- All tool definitions (their schemas, descriptions, examples)

- Conversation history (messages, tool calls, etc)

- The tokens the model is currently generating while reasoning

Every tool definition you add consumes space that the model cannot use for other tasks. In a recent blog post Anthropic showed how an agent is using ~72K tokens for the tool definitions of 50+ MCP tools, and another 5k tokens for the conversation history and system prompt. Altogether, this agent is consuming ~77K tokens before any reasoning has been done.

When the model starts with a 38.5% filled context window (Claude Opus 4.5's default context window size is 200k tokens), you'll leave your agent very little room to do subsequent tool calling and handle multi-step reasoning.

Attention dilution makes the model “compete with itself”

Even when context windows are huge (for example, Gemini 3 has a default context window of 1M tokens), attention mechanisms still struggle with irrelevant or overly verbose tool definitions.

The model has to attend to every token to decide what’s relevant. The more irrelevant or redundant tool definitions you include, the more “distracted” the model becomes.

This leads to:

- Confusion between similar tools

- Misfires (“wrong tool” calls)

- “lost in the middle” failures where the system prompt or earlier instructions are ignored

All of these are not context limit problems, they are an attention competition problem.

Because of these constraints, developers end up doing “context budgeting” as part of their context engineering. This requires them to manually select what tools to include, stripping down tool definition schemas to the bare minimum or avoiding large tool surfaces entirely. This is exactly why the four patterns that follow matter, especially when you need to combine tools from multiple MCP servers in your agent. MCP server composition gives the structure needed to group, layer, and orchestrate tools in a way the model can reliably use them.

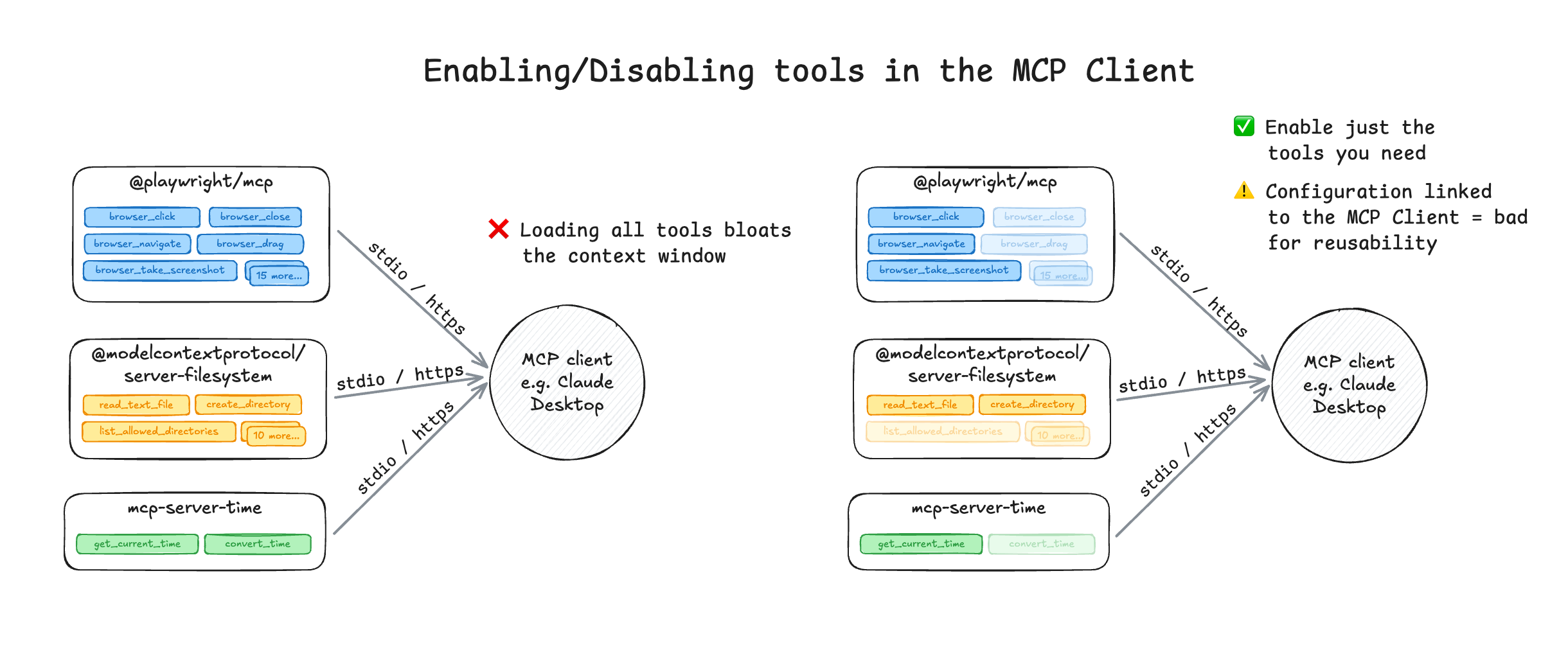

Pattern 1: Tool selection inside the MCP client

By far the easiest way to limit the amount of tools passed to the LLM is to use tool selection within the MCP client, and most chat applications and IDEs already support this pattern directly. Applications like Claude Desktop, ChatGPT, Cursor, and various AI‑powered IDEs let you pick which MCP servers to load, and which tools inside those servers should be active for the current session. This gives you control over what the model can see and prevents the agent, in this case the chat application or IDE, from being overloaded by tools it doesn’t need.

Example of handling tool selection inside the MCP client

Example of handling tool selection inside the MCP clientThis pattern is simple but effective: LLM performance goes up the moment you limit the amount of available tools. Explicitly enabling or disabling tools avoids the two biggest failure modes in tool calling: hallucinated tool calls and overloaded contexts. When the model sees just a handful of clearly defined tools instead of dozens of overlapping ones it’s far less likely to guess, misfire, or call the wrong tool.

Tool selection inside the client is the first layer of control before you start composing servers or building orchestration layers, but far from perfect. You still have to manage the selection manually, and it’s hard to share these configurations with colleagues or clients. And what to think of situations where the tools you need change during the course of your session?

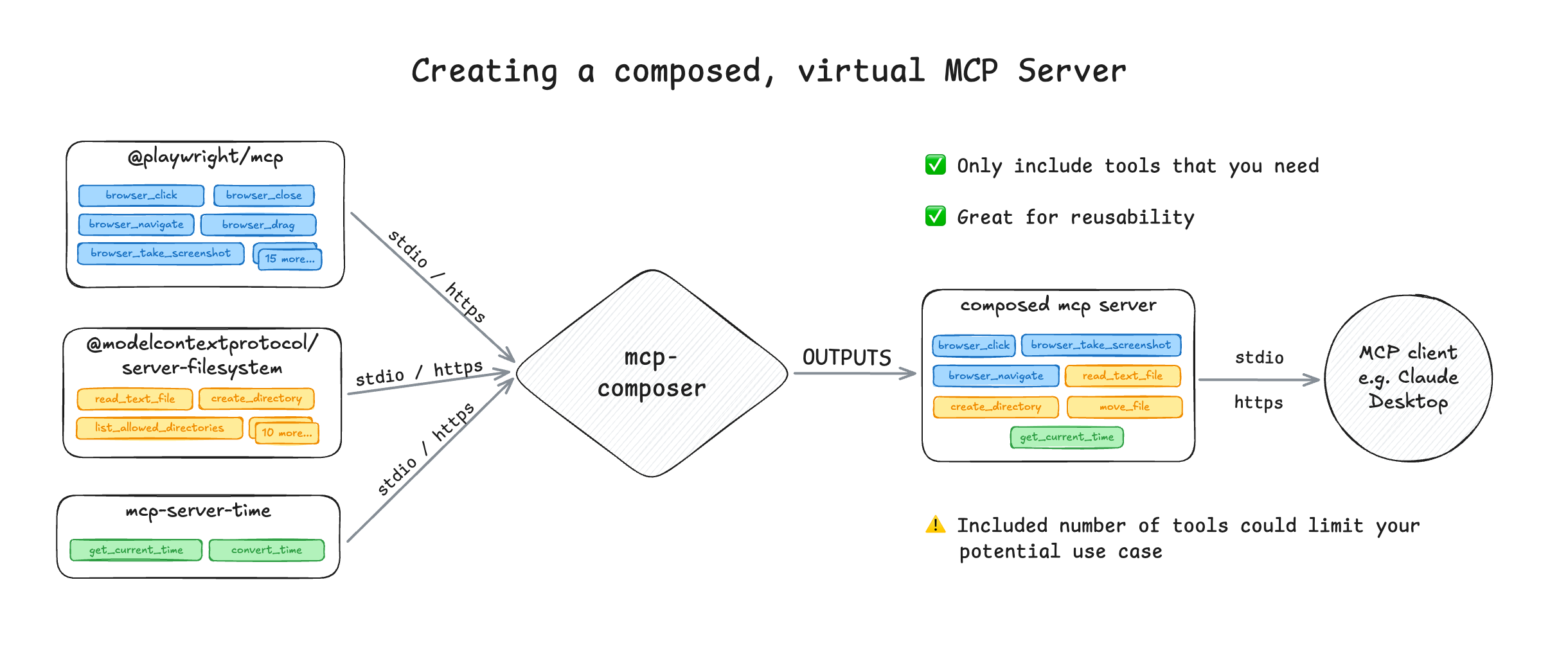

Pattern 2: Composing MCP servers into virtual servers

One step up from using the MCP client to enable or disable tools is creating a new MCP server that exposes only the tools your agent actually needs. Instead of handing the model three or four MCP servers, with dozens of tools it will never use, you compose a virtual MCP server that contains just the relevant ones.

Imagine you're building an agent that needs to scrape a webpage and store the results in a (local) file. You might rely on three different MCP servers to do this (@playwright/mcp, @modelcontextprotocol/server-filesystem and mcp-server-time), but only a subset of their tools matter. By composing a new MCP server with just those tools, you avoid the above discussed problems related to context bloat and tool confusion that increases the chance of wrong tool calls. If not, these three MCP servers alone would have inserted 25+ tool definitions into the context of your agent.

Example of composing MCP servers into (virtual) servers using mcp-composer

Example of composing MCP servers into (virtual) servers using mcp-composer

This maps directly to the earlier mentioned Backend‑for‑Frontend (BFF) pattern in the API world. In a BFF, you create a custom API tailored for a single frontend. If a payment app needs to make several calls to process a transaction, the BFF provides a simplified API surface, sometimes even orchestrating multiple backend calls into one endpoint, that reduces business logic in the client.

MCP server composition works the same way, it becomes the layer that only exposes tool that the agent actually needs. There are two ways to compose MCP servers:

- Build a new server directly using one of the MCP SDKs or a meta‑framework.

- Use an MCP gateway to create a virtual, remote server that proxies and aggregates tools.

Personally, I prefer using a meta‑framework as it gives you the best of both worlds: you can compose servers easily using abstractions without the operational overhead that comes with a gateway (more on MCP gateways later). At IBM we built mcp-composer, which has a CLI to make composing your MCP servers as virtual endpoints easy. It lets developers combine multiple MCP servers (or specific tools from them) into domain‑specific servers without rewriting anything. You pick the tools, define the scope, and expose a single interface your agent can reliably use.

Pattern 3: Dynamic Tool Selection

With dynamic tool selection, you push the responsibility of choosing the right tool down into the server layer. Most tool‑calling mistakes happen because we force the LLM to choose directly from a long list of tool definitions. The model has to read every tool name, description, and schema in its context just to decide which one to call.

Dynamic tool selection lets the MCP server determine which tool should be called from which MCP server. This removes a big amount of overhead from the model and dramatically improves reliability, without giving away control over the available tools.

There are two emerging approaches to handle dynamic tool selection:

- Layered Tool Design

- RAG‑MCP (Retrieval‑Augmented Tool Selection)

Let's break down each of these solutions.

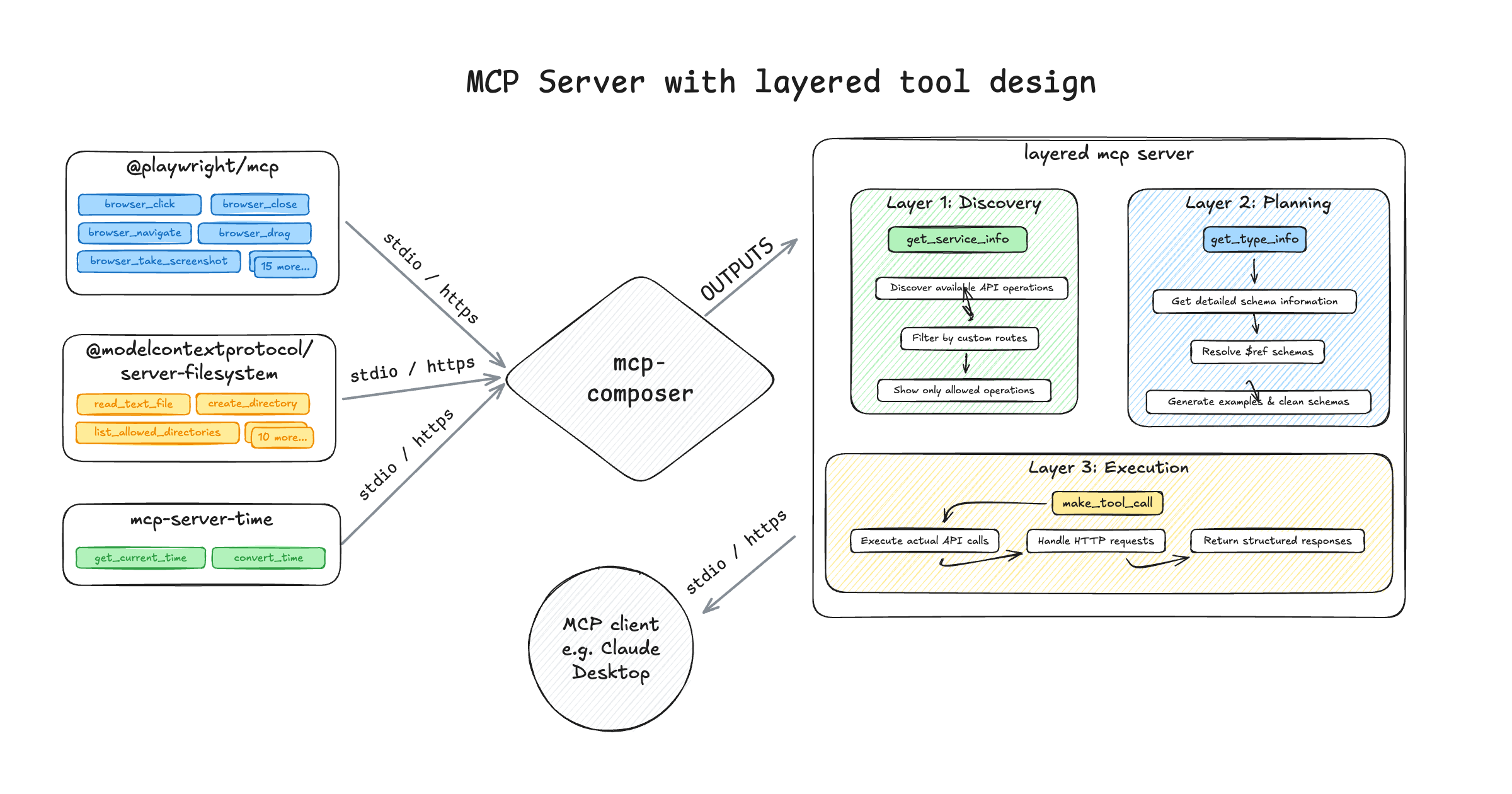

Layered Tool Design

With the layered tool design you "hide" the tool definitions behind layers. The LLM interacts only with a small set of high‑level tools (discovery, planning & execution), and those tools internally call lower‑level tools, bundle logic, or orchestrate multi‑step flows. This is the pattern that the engineering team at Block implemented for Square's payment MCP server, and since has been implemented in various MCP solutions.

Example of Layered Tool Design using mcp-composer

Example of Layered Tool Design using mcp-composer

The layers are designed like this:

- Discovery layer: Returns a short, simplified set of high‑level operations the LLM can choose from. Instead of exposing every tool and schema, this layer prevents the context window from being flooded with unnecessary details.

- Planning layer: Once the LLM selects a tool, the planning layer determines the exact inputs needed. It derives the correct parameters based on the underlying tool definitions, so the model only has to fill in these values.

- Execution layer: Executes the final tool call by routing it to the correct MCP server, along with the validated input parameters.

While a layered MCP server doesn’t technically choose the tool for the LLM, it gives the model a much smaller and more structured surface to choose from. It removes irrelevant information, reduces context bloat, and guides the model toward the correct tool without forcing it to understand every schema. This works especially well for MCP servers that were derived form existing APIs or multi-purpose MCP servers that contain lots of tools.

You can implement this layered tool design with mcp-composer, and even combine tool selection approaches: you can first compose a narrowed‑down tool set into a virtual MCP server, and then apply layered tool design on top of that server to make tool selection even more reliable and easier for the model to use.

RAG‑MCP (Retrieval‑Augmented Tool Selection)

Retrieval Augmented Generation (or RAG) helps LLMs to find the right context from a knowledge base, without bloating the context window with irrelevant information. Think of a situation where you are looking for the cancellation policy in a 34-page contract. Instread of shoving all these pages into the context, the RAG system will retreive only the relevant chunks of information to reduce the context bloat. With RAG-MCP,the knowledge base would be the tool definitions of all your MCP servers, and the MCP server would dynmically select the required tool.

Breakdown of RAG-MCP from a blog post by Writer

Breakdown of RAG-MCP from a blog post by Writer

Instead of loading all tools into the context, the server:

- Embeds each tool definition

- Ranks them by semantic similarity to the user request

- Loads only the most relevant tools into the model’s context

This means the model receives only the tools needed based on the prompt, not everything the MCP server(s) supports. According to the RAG-MCP research paper this approach decreases the amount of tokens spent on tool definitions by over 50% and, based on a benchmark across websearch tools, increases tool selection accuracy by 200%. You can find an example implementation of RAG-MCP on GitHub, based on a blog post by Writer.

Next to this example, you can also find a similar approach in Anthropic's new Tool Search capability. When you build an agent using the Anthropic API, you can pass all your MCP servers in a single request and include a flag that tells Claude whether to use regex or bm25 for tool selection. Instead of loading every tool definition into the prompt, Claude applies either regex matching (executed as Python code) or BM25 (a lightweight retrieval technique) to determine which tools are relevant based on the user’s message.

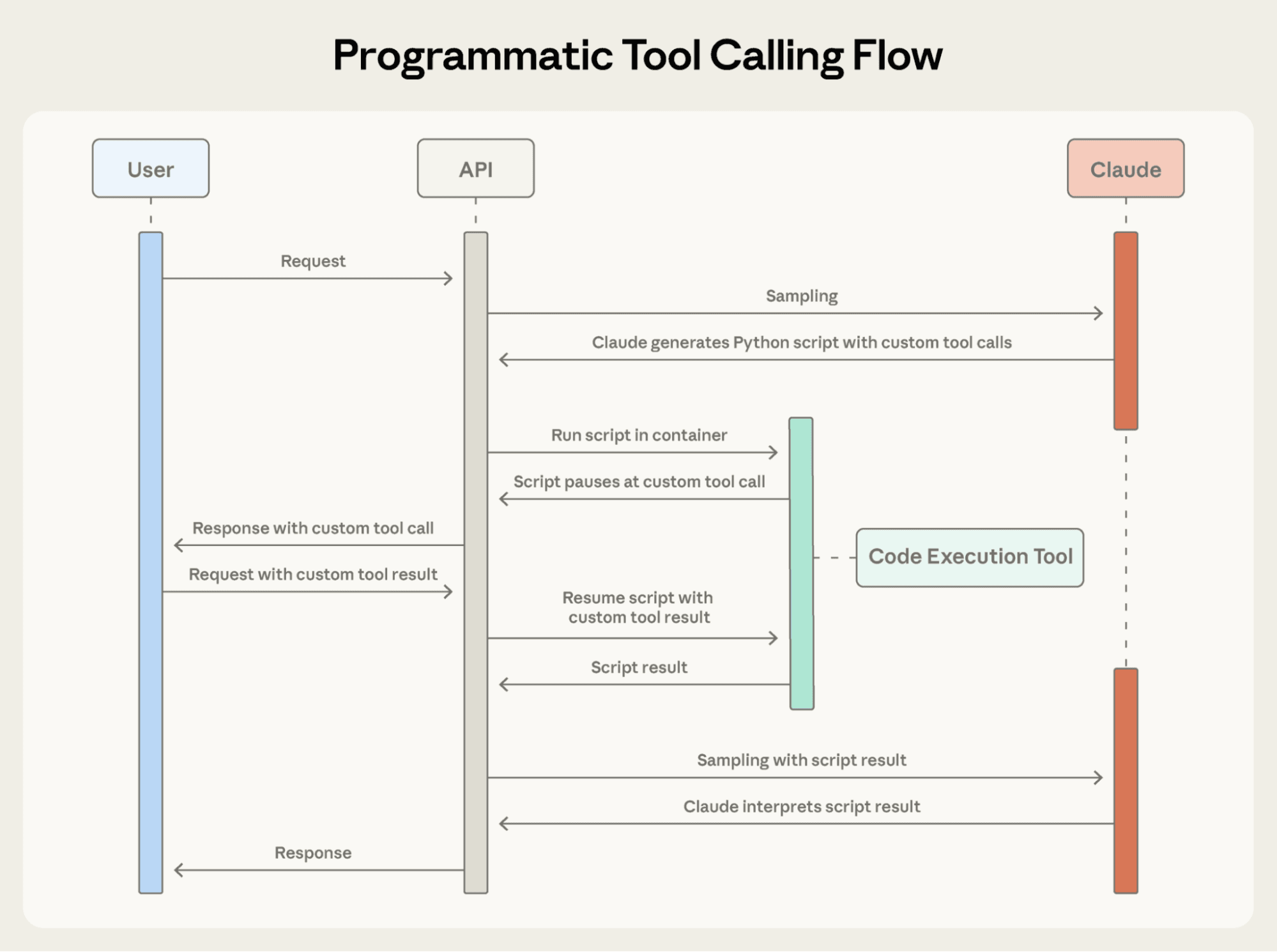

Pattern 4: Programmatic Tool Execution

The final pattern pushes MCP server composition one step further. Instead of asking the LLM or MCP server to select a tool, you let the model generate code that imports and executes the selected tools in a sandboxed environment. So far, this pattern has been implemented by Cloudflare (called "Code Mode") and Anthropic.

Flow of Programmatic Tool Execution as described by Anthropic

Flow of Programmatic Tool Execution as described by Anthropic

Programmatic tool execution makes use of a sandbox with a script generated by the model (usually in Python) to chain tool calls, iterate over results, applies filters, etc. The script is then executed in a runtime that:

- Enforces valid MCP tool schemas

- Prevents unsafe operations

- Returns only the final output back to the model

This pattern significantly decreases the amount of tokens in the context for the LLM as it only needs to call the tool surfacing the sandbox. It could be specially powerful for tasks that involve multiple tool calls that need to chained or require conditional logic, but depending on how you would implement this, there could be additional tokens needed (and added latency) to generate the tool execution script.

Also, the risk with programmatic tool execution is the lack of control developers have over how tools are being called, the possibility of side effects and all sorts of injections. As many developers are trying to tuns probabilistic LLMs into deterministic software, the last thing most them are willing to do is giving up more control.

What About MCP Gateways?

Every enterprise considering adopting MCP is looking at MCP gateways to secure, deploy, version, and route MCP servers in a centralized way, including tracking usage, enforcing usage limits, etc. Similar to API gateways, they are used as the single entry point for an enterprise's developers and clients to interact with their services. However, a lot of MCP gateways do more than proxying or aggregating MCP servers, making the line between a "tool layer" (like a BFF) and a gateway very fine.

That said, not every developer needs a gateway in the traditional sense. Most application developers (now called AI engineers) will get far more value by creating a clean tool layer the agent can rely on, very similar to how frontend developers relied on BFFs to simplify and shape complex backend systems. Gateways, on the other hand, solve operational problems, not design problems. If your tools are badly designed, unstructured, or confusing for the model to use, a gateway won’t fix that problem, but the patterns described in this blog post do.

This is why I believe the future “app layer” for agents won’t be a gateway. It will be a tool composition layer (like mcp-composer), built much closer to where application logic lives. Gateways will still play a role for organizations that need centralized control, but the majority of AI developers will be better served by curating and shaping the tools they expose to their agents first.

If you do end up needing an MCP gateway, check out Context Forge, an open-source MCP and A2A gateway built by a great team at IBM.

To conclude

MCP server composition gives agents the structure and focus they’ve been missing. Tool calling doesn’t break because LLMs can’t use tools, it breaks because we hand them too many tools, expose the wrong ones, or fail to design them properly. The four patterns in this post should give you an idea how to fix your broken agent, and as the MCP specification keeps evolving I'm interested in seeing how some of these patterns are getting incorporated. Not every team needs every pattern, and not everyone needs a gateway. What every team building agents does need is a thoughtful tool layer that mirrors the evolution we saw with APIs, BFFs, and GraphQL.

If you found this blog post helpful, don’t forget to share it with your network. For more content on AI and web development, subscribe to my YouTube channel and connect with me on LinkedIn, X, or Bluesky.